Introduction to Transformer

We introduce the Transformer, a novel network architecture designed for sequence transduction tasks, which entirely eschews recurrence and convolutions, relying solely on attention mechanisms. Traditional sequence models, particularly recurrent neural networks (RNNs) like LSTMs and GRUs, process information sequentially, limiting parallelization and making it challenging to capture long-range dependencies efficiently. While convolutional neural networks (CNNs) offer some parallelization, they often require many layers to connect distant positions. Our motivation was to overcome these inherent sequential constraints and improve the ability to model dependencies regardless of their distance. The Transformer achieves this by drawing global dependencies between input and output positions through an attention mechanism, enabling significantly more parallelization. This design choice has led to superior quality, faster training times, and state-of-the-art results on challenging machine translation tasks, as well as successful generalization to English constituency parsing.

Model Architecture Details

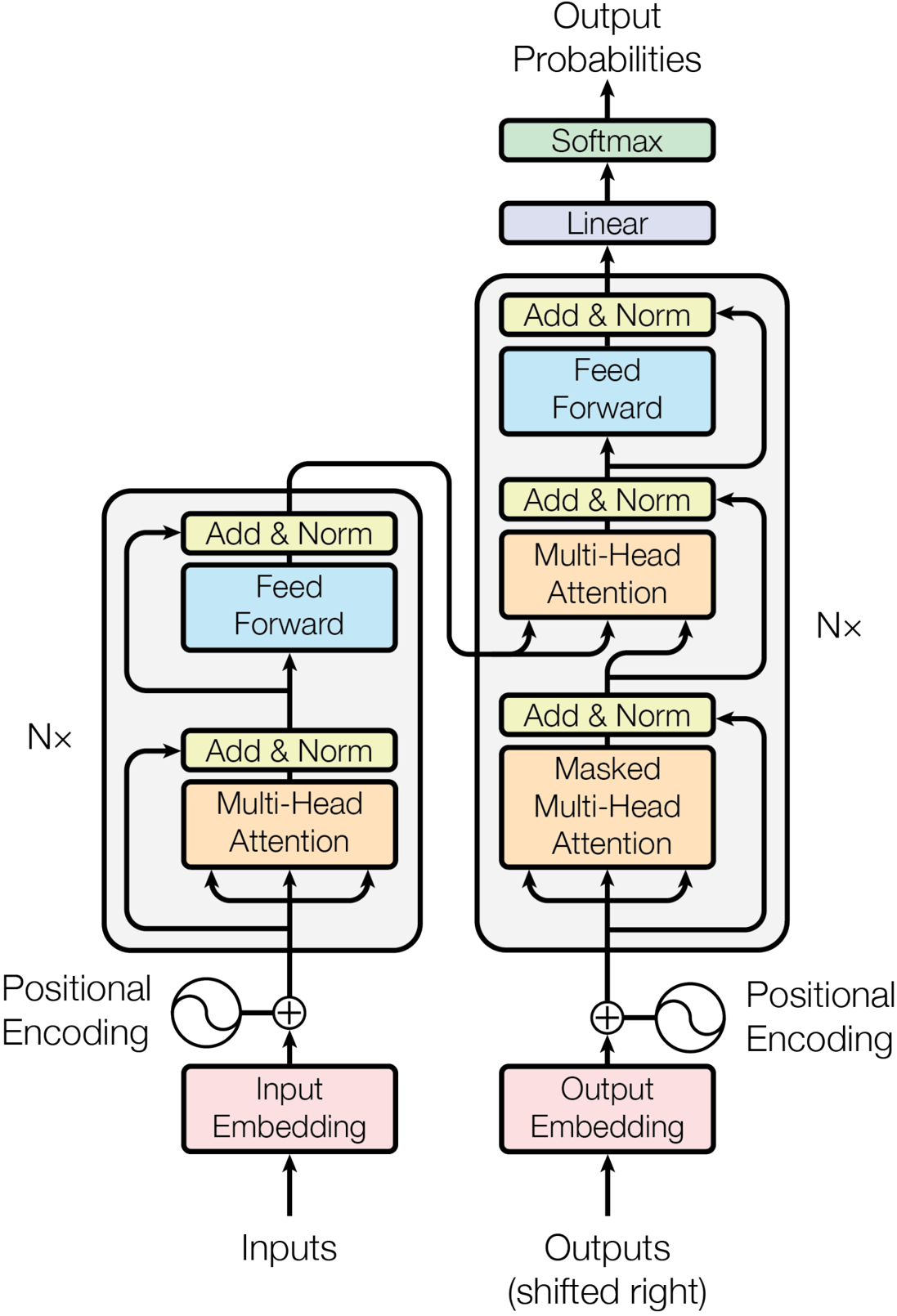

Our Transformer model adopts the standard encoder-decoder structure. The encoder maps an input sequence of symbol representations to a sequence of continuous representations, and the decoder then generates an output sequence one symbol at a time, being auto-regressive by consuming previously generated symbols as input.

The core of our architecture consists of stacked self-attention and point-wise, fully connected layers.

Figure 1: The Transformer - model architecture.

- Encoder: Composed of N=6 identical layers. Each layer has two sub-layers: a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a simple, position-wise fully connected feed-forward network. We incorporate residual connections around each sub-layer, followed by layer normalization. All sub-layers and embedding layers produce outputs of dimension `$d_{model} = 512$`.

- Decoder: Also N=6 identical layers. It includes the two sub-layers from the encoder, plus a third multi-head attention sub-layer that performs attention over the encoder's output. We apply residual connections and layer normalization here too. Crucially, the decoder's self-attention sub-layer is masked to prevent attending to subsequent positions, preserving the auto-regressive property.

Attention Mechanism:

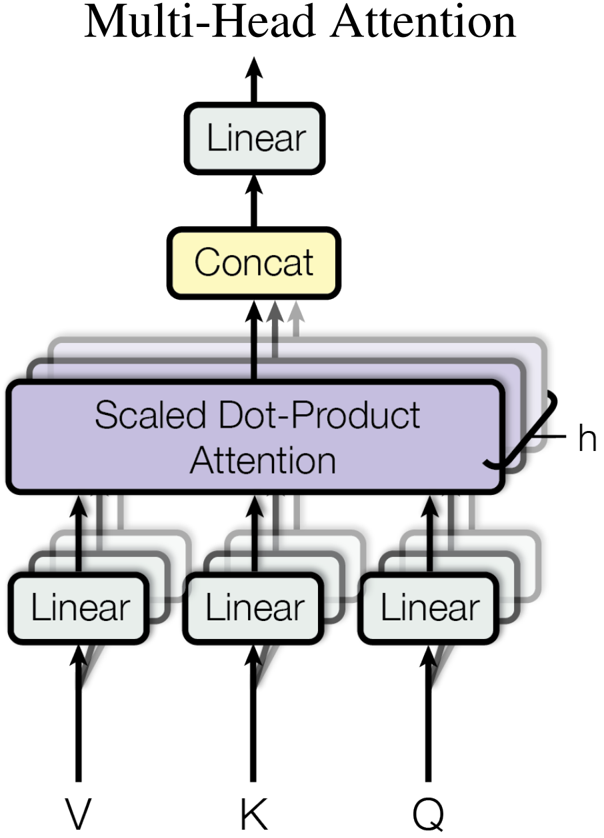

An attention function maps a query and a set of key-value pairs to an output. The output is a weighted sum of values, with weights determined by the compatibility of the query with corresponding keys.

Figure 2: (left) Scaled Dot-Product Attention. (right) Multi-Head Attention consists of several attention layers running in parallel.

- Scaled Dot-Product Attention: This is our specific attention function. Given queries (Q), keys (K) of dimension `$d_k$`, and values (V) of dimension `$d_v$`, we compute the attention output as: $$Attention(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}(Q K^T / \sqrt{d_k}) V$$ We scale the dot products by `$1/\sqrt{d_k}$` to counteract large magnitudes that can push the softmax into regions with extremely small gradients, especially for large `$d_k$`. This dot-product attention is faster and more space-efficient than additive attention due to optimized matrix multiplication.

- Multi-Head Attention: Instead of a single attention function, we found it beneficial to linearly project the queries, keys, and values `$h$` times with different learned linear projections. We then perform the attention function in parallel on these projected versions, concatenating the `$h$` resulting `$d_v$`-dimensional outputs and projecting them once more. This allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions, which a single attention head might inhibit through averaging. In our work, we use `$h=8$` parallel attention layers, with `$d_k = d_v = d_{model} / h = 64$`.

The Transformer employs multi-head attention in three ways:

- Encoder-Decoder Attention: Queries from the previous decoder layer attend to keys and values from the encoder's output, allowing the decoder to focus on relevant parts of the input sequence.

- Encoder Self-Attention: Each position in the encoder attends to all positions in the previous encoder layer.

- Decoder Self-Attention: Each position in the decoder attends to all preceding positions in the decoder, with masking to prevent attending to future tokens.

Position-wise Feed-Forward Networks: Each layer in the encoder and decoder also contains a fully connected feed-forward network, applied identically and separately to each position. This network consists of two linear transformations with a ReLU activation: $$FFN(x) = \max(0, x W_1 + b_1) W_2 + b_2$$ The input and output dimensionality is `$d_{model} = 512$`, with an inner-layer dimensionality of `$d_{ff} = 2048$`.

Embeddings and Positional Encoding: We use learned embeddings to convert input and output tokens into `$d_{model}$`-dimensional vectors. To account for the sequence order, as our model lacks recurrence or convolution, we add "positional encodings" to the input embeddings at the bottoms of the encoder and decoder stacks. We use sine and cosine functions of different frequencies: $$PE(\text{pos}, 2i) = \sin(\text{pos} / 10000^{2i/d_{model}})$$ $$PE(\text{pos}, 2i+1) = \cos(\text{pos} / 10000^{2i/d_{model}})$$ This choice allows the model to easily learn to attend by relative positions. We found that learned positional embeddings yielded nearly identical results, but the sinusoidal version may extrapolate better to longer sequences.

Our self-attention layers connect all positions with a constant number of sequential operations, offering a significant advantage over recurrent layers which require `$O(n)$` sequential operations, especially for longer sequences.

| Layer Type | Complexity per Layer | Sequential Operations | Maximum Path Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Attention | O(n2 · d) | O(1) | O(1) |

| Recurrent | O(n · d2) | O(n) | O(n) |

| Convolutional | O(k · n · d2) | O(1) | O(logk(n)) |

| Self-Attention (restricted) | O(r · n · d) | O(1) | O(n/r) |

Training Methodology

We trained our models on several standard datasets. For machine translation, we used the WMT 2014 English-German dataset (approximately 4.5 million sentence pairs, 37,000 shared byte-pair encoding tokens) and the WMT 2014 English-French dataset (36 million sentences, 32,000 word-piece vocabulary). For English constituency parsing, we trained on the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) portion of the Penn Treebank (about 40,000 training sentences, 16,000 tokens) and in a semi-supervised setting using larger corpora (approximately 17 million sentences, 32,000 tokens).

Our training was performed on a single machine equipped with 8 NVIDIA P100 GPUs. Base models were trained for 100,000 steps (about 12 hours), with each step taking approximately 0.4 seconds. Our larger "big" models were trained for 300,000 steps (3.5 days), with each step taking about 1.0 second.

We utilized the Adam optimizer with `$\beta_1 = 0.9$`, `$\beta_2 = 0.98$`, and `$\epsilon = 10^{-9}$`. The learning rate was dynamically adjusted, increasing linearly for the first `$warmup\_steps = 4000$` and then decreasing proportionally to the inverse square root of the step number.

To regularize our models, we employed three techniques:

- Residual Dropout: Applied to the output of each sub-layer before residual addition and normalization, and also to the sums of embeddings and positional encodings. For the base model, we used a dropout rate `$P_{drop} = 0.1$`.

- Label Smoothing: A value of `$\epsilon_{ls} = 0.1$` was used, which, while hurting perplexity, improved accuracy and BLEU score.

Performance Evaluation

Our Transformer models achieved state-of-the-art results across various tasks, demonstrating superior performance and efficiency.

Machine Translation:

- English-to-German (WMT 2014): Our big Transformer model achieved a new state-of-the-art BLEU score of 28.4, surpassing the best previously reported models (including ensembles) by over 2.0 BLEU. Even our base model outperformed all prior published models and ensembles, at a significantly reduced training cost.

- English-to-French (WMT 2014): Our big model established a new single-model state-of-the-art BLEU score of 41.8, achieving this at less than a quarter of the training cost of the previous best models.

These results highlight the Transformer's ability to deliver higher quality translations with substantially less training time compared to recurrent or convolutional architectures.

| Model | BLEU | Training Cost (FLOPs) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN-DE | EN-FR | EN-DE | EN-FR | |

| ByteNet | 23.75 | |||

| Deep-Att + PosUnk | 39.2 | 1.0 · 1020 | ||

| GNMT + RL | 24.6 | 39.92 | 2.3 · 1019 | 1.4 · 1020 |

| ConvS2S | 25.16 | 40.46 | 9.6 · 1018 | 1.5 · 1020 |

| MoE | 26.03 | 40.56 | 2.0 · 1019 | 1.2 · 1020 |

| Deep-Att + PosUnk Ensemble | 40.4 | 8.0 · 1020 | ||

| GNMT + RL Ensemble | 26.30 | 41.16 | 1.8 · 1020 | 1.1 · 1021 |

| ConvS2S Ensemble | 26.36 | 41.29 | 7.7 · 1019 | 1.2 · 1021 |

| Transformer (base model) | 27.3 | 38.1 | 3.3 · 1018 | |

| Transformer (big) | 28.4 | 41.8 | 2.3 · 1019 | |

English Constituency Parsing:

We successfully applied the Transformer to English constituency parsing, a task with strong structural constraints and often longer outputs. Despite minimal task-specific tuning, our 4-layer Transformer with `$d_{model} = 1024$` performed remarkably well.

- WSJ only: Achieved 91.3 F1 score, outperforming the BerkeleyParser even with limited training data.

- Semi-supervised: Achieved 92.7 F1 score, yielding better results than most previously reported models, with the exception of the Recurrent Neural Network Grammar.

Model Variations and Ablation Studies:

We conducted extensive ablation studies to understand the impact of different architectural components:

| N | dmodel | dff | h | dk | dv | Pdrop | εls | train steps | PPL (dev) | BLEU (dev) | params × 106 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| base | 6 | 512 | 2048 | 8 | 64 | 64 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 100K | 4.92 | 25.8 | 65 |

| (A) | 1 | 512 | 512 | 5.29 | 24.9 | |||||||

| 4 | 128 | 128 | 5.00 | 25.5 | ||||||||

| 16 | 32 | 32 | 4.91 | 25.8 | ||||||||

| 32 | 16 | 16 | 5.01 | 25.4 | ||||||||

| (B) | 16 | 5.16 | 25.1 | 58 | ||||||||

| 32 | 5.01 | 25.4 | 60 | |||||||||

| (C) | 2 | 6.11 | 23.7 | 36 | ||||||||

| 4 | 5.19 | 25.3 | 50 | |||||||||

| 8 | 4.88 | 25.5 | 80 | |||||||||

| 256 | 32 | 32 | 5.75 | 24.5 | 28 | |||||||

| 1024 | 128 | 128 | 4.66 | 26.0 | 168 | |||||||

| 1024 | 5.12 | 25.4 | 53 | |||||||||

| 4096 | 4.75 | 26.2 | 90 | |||||||||

| (D) | 0.0 | 5.77 | 24.6 | |||||||||

| 0.2 | 4.95 | 25.5 | ||||||||||

| 0.0 | 4.67 | 25.3 | ||||||||||

| 0.2 | 5.47 | 25.7 | ||||||||||

| (E) | positional embedding instead of sinusoids | 4.92 | 25.7 | |||||||||

| big | 6 | 1024 | 4096 | 16 | 0.3 | 300K | 4.33 | 26.4 | 213 |

- Multi-Head Attention: We found that while single-head attention performed worse, too many heads also led to a drop in quality, indicating an optimal balance.

- Attention Key Size (`$d_k$`): Reducing `$d_k$` negatively impacted model quality, suggesting that determining compatibility is a complex task.

- Model Size: As expected, larger models generally yielded better performance.

- Dropout: Dropout proved to be very effective in preventing overfitting.

- Positional Encoding: Our sinusoidal positional encodings produced nearly identical results to learned positional embeddings, validating our choice for better extrapolation.

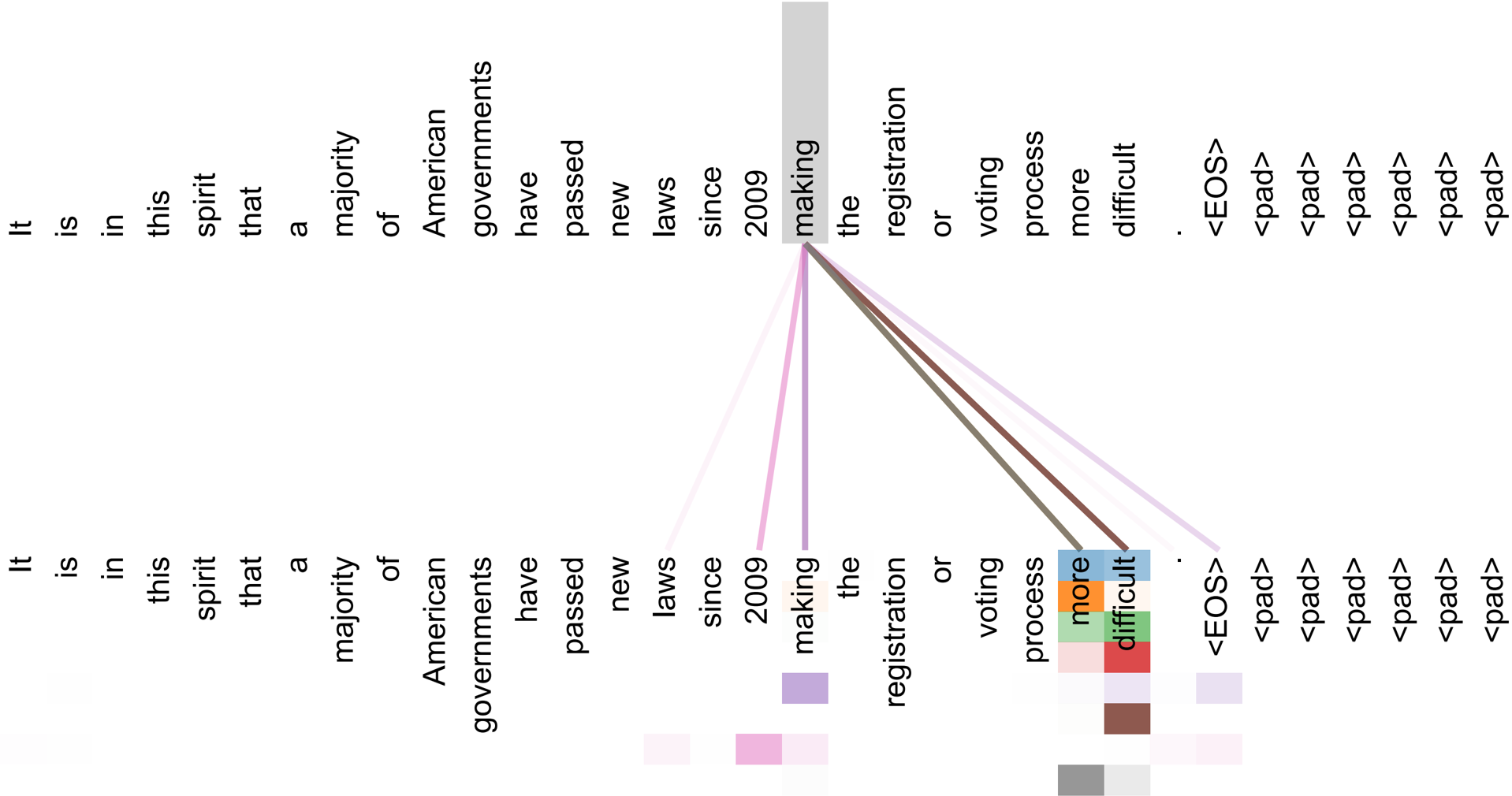

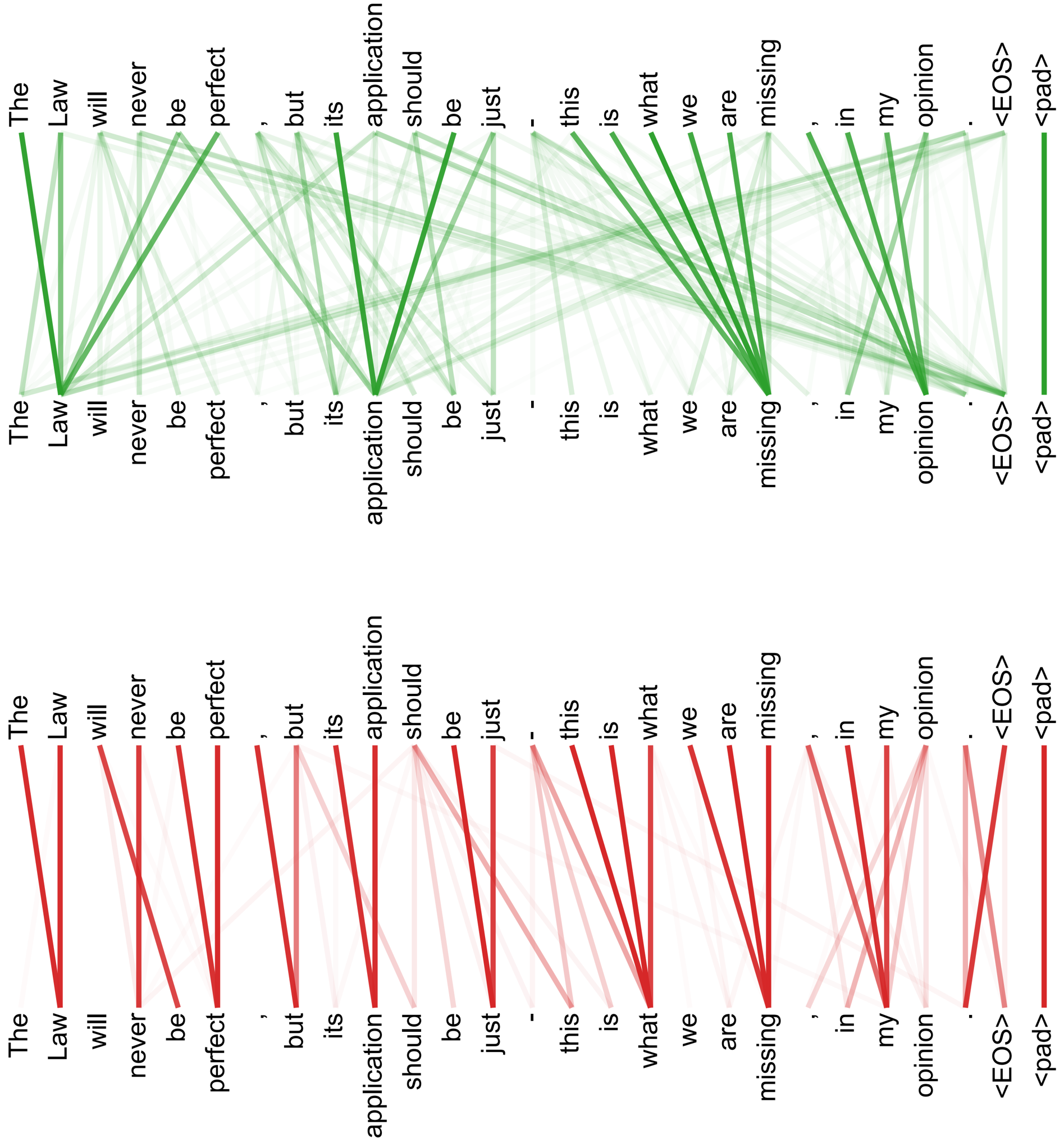

Furthermore, we observed that individual attention heads often learn to perform distinct tasks, exhibiting behaviors related to the syntactic and semantic structure of sentences, such as attending to long-distance dependencies or performing anaphora resolution. This provides valuable interpretability into the model's decision-making process.

Figure 3: An example of the attention mechanism following long-distance dependencies in the encoder self-attention in layer 5 of 6. Many of the attention heads attend to a distant dependency of the verb 'making', completing the phrase 'making...more difficult'. Attentions here shown only for the word 'making'. Different colors represent different heads. Best viewed in color.

Figure 4: Two attention heads, also in layer 5 of 6, apparently involved in anaphora resolution. Top: Full attentions for head 5. Bottom: Isolated attentions from just the word 'its' for attention heads 5 and 6. Note that the attentions are very sharp for this word.

Figure 5: Many of the attention heads exhibit behaviour that seems related to the structure of the sentence. We give two such examples above, from two different heads from the encoder self-attention at layer 5 of 6. The heads clearly learned to perform different tasks.

Summary & Outlook

In this work, we introduced the Transformer, a groundbreaking sequence transduction model that relies entirely on attention mechanisms, completely replacing the recurrent and convolutional layers traditionally used in encoder-decoder architectures. Our key contribution is demonstrating that an architecture built solely on attention can achieve state-of-the-art performance while offering significant advantages in training speed and parallelization.

The Transformer has set new benchmarks in machine translation, achieving superior BLEU scores on both WMT 2014 English-to-German and WMT 2014 English-to-French tasks, often at a fraction of the training cost of previous state-of-the-art models, including ensembles. We also successfully demonstrated its generalization capabilities by applying it to English constituency parsing, where it performed surprisingly well with minimal task-specific tuning.

We are incredibly excited about the future potential of attention-based models. Our immediate plans include extending the Transformer to problems involving other input and output modalities beyond text, such as images, audio, and video. We also aim to investigate local, restricted attention mechanisms to efficiently handle very large inputs and outputs. Another important research goal is to explore methods for making sequence generation even less sequential, further enhancing the parallelization benefits of our approach. The code used to train and evaluate our models is publicly available, fostering further research and development in this promising area.